Mythbusting (or not?): Irish Kate & the Great Fire

Note: This topic remains debated and this article is my understanding from the research that I have done, compiled, and present to you here. I find nothing compelling me to believe that Kate caused the fire, but encourage anyone reading this to come to your own conclusion. And honestly, we may never know the truth…

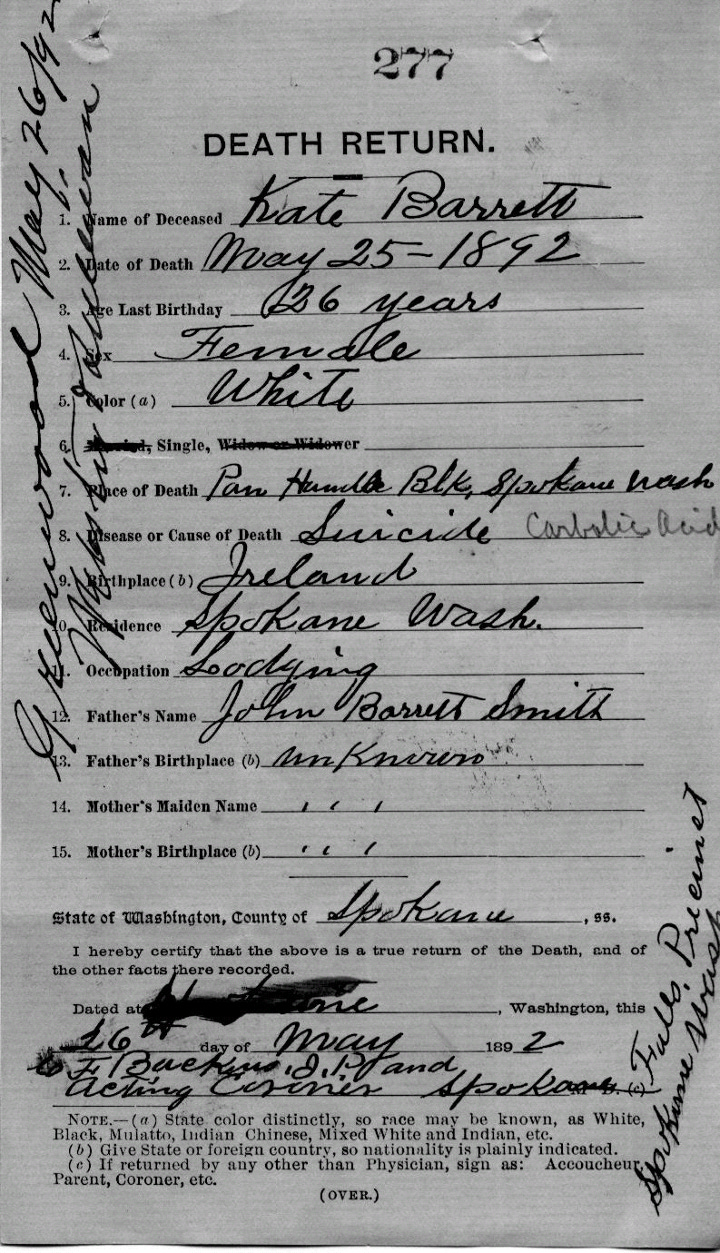

Not much is known about the early years of the life of Kate Barrett, an Irish immigrant known during the fledgling years of Spokane, Washington as "Irish Kate". “Irish Kate” was one name in a sea of colorful monikers for the sporting women of Spokane. While some women achieved certain notoriety in the local newspapers, Kate seemed to have kept to herself and kept her name out of the papers for the most part, until her death.

Kate was living in Spokane when the Great Fire broke out on August 4, 1889, leveling buildings and homes in what is today's business district and displacing hundreds of people who lived in the 32-block burn area. After the flames ceased ravaging the city, speculation began to buzz about what exactly started the fire, but there seemed to be no definite source. The two possibilities that had been settled on were that it either started by a kitchen fire or from the sparks of a train passing through on Railroad Avenue.

In 1937, the Works Progress Administration (WPA) formed the Federal Writers' Project, their most recognized project, established with the goal to create jobs for people with the production of a set of books called The American Guide Series. The books were part travel guide and part almanac, geared at human interest. It contained information, both current and historical, illustrations, maps, and photos that promoted all 48 states at the time, plus Alaska. Each state was charged with creating and publishing their own book in the series with the funding provided by the WPA.

W.E. Aitchison, a traffic safety supervisor in Spokane, was assigned to supervise the project in Spokane and tasked research technicians with telling the story of Spokane’s captivating past. Part of that project turned into an investigation into the cause of the Great Fire in 1889 and to solve, once and for all, what started the historic fire nearly half a century earlier. When the 1937 version of “Washington: A Guide to the Evergreen State” was published, readers finally got to read what was discovered about the origin of the fire. Much to the chagrin of the citizens of Spokane, who had hoped that some lost clues had been found in the case from some of the aged pioneers that were still alive to tell their story, the book alleged that the fire had started in the room of Irish Kate in a lodging house above Sam Wolfe’s saloon on Railroad Avenue, just west of Post Street. The story was not a result of the Feds’ investigation, but a regurgitation of a news article published in the August 4, 1924 Spokesman-Review claiming to be a first-hand account from a commercial painter named Henry Sundahl, an aggressively opinionated prohibition supporter who claimed, “I think I can safely say that whisky was the real cause of the Spokane fire…”. In the article, Sundahl claims that Kate personally confessed to him that the fire started shortly after she had spurned the advances of a drunken man while having a drink in the saloon. Sundahl claims that she told him that she then finished her drink in the saloon and retreated to her room upstairs. Once in her room, she allegedly placed her curling iron atop the chimney of an oil lamp to heat it. Shortly thereafter, the man from downstairs burst in her room. Demanding that he leave, the confrontation between her and the man escalated into a scuffle which resulted in the iron and the oil lantern being knocked down to the floor. The story continues saying that the lace draperies in Kate’s room caught fire with flames rapidly spreading to the wall before rushing straight to the roof, then jumping to neighboring buildings, igniting the wooden structures like tinder in the hot, dry summer air creating an inferno big enough to then swallow larger buildings of granite and brick. Sundahl’s claim then alleges that Kate told him that she had grabbed some of her things and gone into another building, hid inside, and cowered in shame hoping that no one ever learned that she had started the fire. Well, except to confide in a man who, it seemed, would have eagerly wielded the powerful story as a weapon in his ongoing crusade against liquor, yet remained silent in the midst of prohibition.

Aitchison’s publication of Sundahl’s version of events caused a tremendous amount of outrage in the people of Spokane who were proudly represented by the Spokane Daily Chronicle. The most vocal of the people outraged were the remaining pioneers that were in the chaos of it all on that fateful day in 1889—the actual eye witnesses to the fire. The Chronicle alluded to a widespread feeling among the people of Spokane that “the Feds”, who were not living in Spokane, and most definitely not in Spokane 48 years previously, had come in and rewritten their history, forcing people to have to choose a version to tell future generations.

The story that Irish Kate started the fire could never be proven as there were no witnesses and absolutely no tangible evidence to substantiate it, only the hearsay of one man. Officially, the cause remains unknown to this day. That, unfortunately, has never stopped the story being told, leaving Kate unwittingly immortalized in Spokane lore.

The Real Kate Barrett

Kate's life was plagued with struggle and sorrow. She left Ireland for America alone, with no family contact, in a city far away. She often spoke of wanting to live a normal and virtuous life and even attempted to improve her circumstances on a couple of occasions. In March of 1889, only months before the fire, Reverend Jonathan Edwards officiated a marriage between Kate and a man named George Brooks. The marriage was short-lived and soon Kate was back to the sordid life she had wanted to leave behind.

It wasn’t long before Kate met harness shop owner Ole R.“Ollie” Nestos and began an affair with him. Little is known about their relationship. Nestos was considered an esteemed and respected businessman of the city. One could speculate that a man of such standing wouldn't wish to carry on publicly with a woman with a reputation such as Kate's. Although, by all appearances, it did seem that he had a genuine affection for Kate. Kate, however, seemed tormented by the relationship. Perhaps it could be said that she saw him as her ticket to a better life, away from the cribs and unscrupulous men and was frustrated that he didn’t make any move toward marriage. Despite appearances and misconceptions, it seemed that Kate genuinely wanted love, family, and a place to call home. Perhaps she was plagued by loneliness. She was frequently pained in her relationship with Ollie, sometimes speaking to friends about her desire to end her life.

On the early morning of August 19, 1891, a fire broke out at Ole Nestos’ new building on Main Avenue between Division and Pine Streets. Part of the main floor of the building was occupied by Otto Baeumle's Bottling Works and the upstairs portion of the building was discovered to have a sole occupant living in the rooms upstairs: Irish Kate. It was reported that a very determined effort was made by an arsonist to burn the building down that night and had started in a barrel beneath the stairwell. No one was ever arrested for the fire.

Insurance money from the fire allowed Kate to move into a lodging house in the Panhandle Block on the northeast corner of Post Street and Main Avenue. She continued her secret relationship with Ollie Nestos. Her friends recalled her more regularly in turmoil over the relationship at this point. In the first few weeks of May 1892, she had become desperate and spoke more frequently of taking her life. She just couldn't find her way out of the life she felt trapped in.

On the 25th of May, Kate appeared at the door of her friend and neighbor Georgie Brooks, a performer at the Theater Comique at the other end of the block. She had been crying. She told Georgie that she and Ollie “had quit”. She sent a messenger to return the ring and necklace gifted to her from Ollie. The messenger relayed to Ollie that he believed that Kate was either drunk or crazy. Ollie immediately left his office and went to Kate's to check on her and find out why she had returned the jewelry that he had given to her. She responded “For you to throw them in the river.”

As Ollie and Georgie stood in the hallway talking to her, a despondent Kate went into her room and returned with a glass of water and a vial of carbolic acid. Standing near the doorway to her room, she put the glass to her lips and drank its contents before anyone could react.

“Goodbye, Ollie. Goodbye, Georgie,” she said sorrowfully, “I am going to die.” She turned and walked back into her room. Georgie followed her while Ollie and another neighbor ran to summon for help. Doctors Doolittle and Penn and arrived and looked Kate over as she lie on the floor in agony. Almost immediately they knew there was nothing that they could to save Kate—she was already succumbing to the deadly effects of the poison.

Kate took her last breath at 11:17 am, after 37 agonizing minutes of pain caused from the poison she drank. For Kate, it was probably a small penance to be free from a life filled with sorrow, loneliness, and broken dreams. She was only 26 years old.

Kate Barrett was laid to rest in an unmarked grave in Greenwood Cemetery's “potter's field”, now known as the non-endowed section. No one ever came forward to claim her remains.

Kate Barrett was laid to rest in an unmarked grave in Greenwood Cemetery's “potter's field”, now known as the non-endowed section. No one ever came forward to claim her.

Citations

Jonathan Edwards An Illustrated History of Spokane Country, State of Washington W.H. Lever, Publisher, 1900

Newspapers.com

Moynahan, Jay M. Red Light Revelations: Unveiling Spokane’s Risque Past, 1885 to 1905. Spokane: Chickadee Publishing, 1999

Ancestry.com

Washington State Digital Archives

©2020-2025 E. Deasy unless otherwise noted.